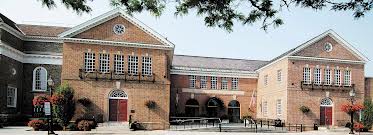

The stories approach mythology. Babe Ruth justified a Depression-era salary larger than President Herbert Hoover’s with the wry comment that he had a better year. A dying Lou Gehrig declared himself “the luckiest man in the world.” Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey integrated baseball seven years before Brown v. Board of Education. Cal Ripken played 2,632 consecutive games over 16 years. These stories and the institution that celebrates them, the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, are as ingrained in the American cultural psyche as apple pie and, well, baseball.

As a museum the Hall of Fame provides a sensory connection to the history of baseball from its origins as a pastoral response to the industrial revolution, through the Civil War when Union and Confederate troops played together, through Jim Crow, two World Wars, 1960s race riots, and into the 2009 World Baseball Classic. The Hall celebrates not only baseball, but American culture as seen through the lens of baseball. The Hall of Fame’s collection of artifacts ranges from the 1839 Doubleday baseball that was the basis for the museum’s Cooperstown, NY location to the jersey worn by White Sox pitcher Mark Buehrle during his July 23, 2009 perfect game.

Most of the Hall’s collection consists of objects that could be classified as ephemera – baseballs, bats, uniforms, contracts, sheet music, scrapbooks - yet how many of the museum’s 350,000 annual visitors consider the lengths to which a non-profit educational institution, funded by ticket and gift shop sales, individual donors, and foundations, must go to preserve its fragile piece of cultural heritage?

Like all cultural heritage institutions, the Hall of Fame must allocate its resources of time, energy, money, and space among exhibitions, research requests, and storage. As a repository, the Hall has a duty to preserve the items in its charge, and director of collections Susan MacKay noted the particular challenges presented by the Hall’s broad range of artifacts. She illustrated her point by listing the collection’s 1.2 million documents, 500,000 photographs, 12,000 hours of recorded video and sound, and 38,000 three-dimensional objects made of leather, wood, silk, wool, and other materials. All of the items in the collection were donated, and the Hall accepts every donated three-dimensional object, she said.

As Hall of Fame librarian Jim Gates put it, “Any conservation issue known to library science must be dealt with by the Hall.”

The great enemies of archival and library artifacts are temperature, humidity, light, pollution, and human handling. The Northeast Document Conservation Center in Andover, MA warns that heat accelerates deterioration; high relative humidity promotes mold growth and chemical reactions; light weakens cellulose fibers and fades dyes; particulate contaminants soil and abrade surfaces; and gases spark chemical reactions. Wear and tear, sometimes literally, from use can accelerate deterioration. In its series of preservation leaflets on its website, www.nedcc.org, NEDCC asserts that the rate of deterioration of archival materials approximately doubles with each temperature increase of 18 degrees Fahrenheit. NEDCC also underscores the importance of stable climate conditions as fluctuations in heat and humidity can dramatically stress materials.

What does this mean for the Hall of Fame?

NEDCC recommends temperature no higher than 70° F and relative humidity between 30% and 50%. According to www.wunderground.com Cooperstown’s temperature ranges from the mid 80s in summer to below zero in winter, and humidity ranges from high 90s in summer to low 50s in winter. To combat the challenges of Cooperstown’s ambient climate, MacKay said the Hall employs a computer controlled and monitored climate control system that maintains a consistent environment of 68° F and 47% relative humidity. It also filters gas and particulate pollution. In addition to the system costs, the Hall spends approximately $50,000 per month on utilities. The system also must maintain the same environmental conditions in buildings of varying age, from the original edifice constructed in 1939 to the 1994 library addition. Although renovations like the $20 million project completed in 2005 have upgraded the environmental controls in all of the Hall’s buildings, the older structures still present a challenge of constant facilities maintenance, MacKay said.

The Hall of Fame’s museum mission is a built-in preservation complication. The museum is open seven days a week, 9 am to 9 pm during the summer and 9 am to 5 pm the rest of the year. Nearly 1,000 visitors per day walk through the museum’s front doors, which MacKay identified as one of the Hall’s biggest environmental challenges. “Every time the doors open it stresses the temperature and humidity controls. They open onto the lobby where we have a very large painting, so that is exposed to temperature and light stresses each time the doors open,” she said.

Light threatens more than items in the lobby because while natural light is most damaging, heat and ultraviolet energy emitted from incandescent and florescent lighting is also harmful. NEDCC recommends that items only be exposed to light when in use, but in a sense, items on exhibition are in constant use. MacKay said the Hall’s exhibition spaces use fiber optic lighting, which conducts no heat or UV radiation. In some cases, the Hall protects documents or photographs by using facsimiles in exhibits. Three-dimensional artifacts not on exhibit, including donations awaiting processing, are kept in a dark 2,772 square foot storage area, one of six archival storage vaults, each designated for a particular type of material.

NEDCC also recommends that archival items receive limited handling. The movement toward interactive exhibits conflicts with that goal, and the institution must balance its interests. For example the Hall “used to allow the public to sit on actual stadium seats and benches but it became a hazard because of the wear and tear,” MacKay said.

Even with those kinds of issues, handling is less a problem for the museum than it is for the library. The library fields 60,000 research requests a year for, as Gates said, “Everyone from third graders to PhD candidates. From authors and team executives to drunks in bars with $20 riding on a bet.” Many of the reference requests are received and answered via phone calls or emails, but thousands of researchers each year come to the A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center to view an item in the library’s collection.

The library employs policies and procedures designed to mitigate damage from the researchers’ handling of materials. It is a closed stack library, meaning that only library staff has access to the materials. Gates added that the stacks are closed to most of the Hall of Fame staff much less researchers. Particularly rare or fragile items have been microfilmed for use as surrogates, but Gates stressed that the library keeps the originals. Researchers make an appointment at least a week in advance of their visit. When they arrive a library staff member brings the requested materials to them in the reading room, which seats a maximum of 20 people and is monitored at all times by a staff member and a live video feed. In addition Gates assesses the appropriateness of the use requested.

“We don’t want third-graders leafing through Mrs. Gehrig’s scrapbooks just for fun,” Gates said, but he added that some risk must be accepted because the library has collected items so they can be used.

Because of that use and because of natural chemical processes, even with handling limitations and environmental controls in place, some artifacts occasionally need a little love. While the Hall has no conservators on staff, they have relationships with contracted conservators. For example, the Hall uses NEDCC for its paper conservation needs. MacKay said that once a year, artifacts are transported to conservation labs for repairs and stabilization.

“We practice conservation not restoration,” she said, “We are interested in the item’s longevity. We do not wish to remove anything intrinsic to the piece.”

Wear in the pocket of a glove, nicks on the barrel of a bat, split seams on a baseball are all part of those items’ stories and the larger stories which those items represent. The stories draw all manner of visitors to the village of Cooperstown. In the 15 years Jim Gates has been the Hall of Fame librarian he has served hall of famers, presidents, celebrities, Japanese fans, children, senior citizens. Many of them come back year after year.

“One of the perks of the job,” Gates said, “is that you get to know people on a first name basis that you would otherwise have never met. People from all backgrounds and walks of life come to the Hall because of a commonly shared love of baseball, and they use it to get to know each other.”

The work of the Hall of Fame preserves not only things, but that experience for generations to come.

References

http://web.baseballhalloffame.org/museum/history.jsp retrieved July 31, 2009

http://web.baseballhalloffame.org/museum/president.jsp retrieved August 6, 2009

Http://www.nedcc.org/resources/leaflets.list.php retrieved August 6, 2009

http://www.wunderground.com retrieved July 31, 2009

Interview with Susan MacKay, director of collections, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum August 7, 2009

Interview with Jim Gates, librarian, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum August 10, 2009

© 2013 Robert McKercher. All rights reserved.

Safe At Home:

How the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum Preserves Baseball History

Originally published November 2010